Falling, failing, flying

Published: April 2025

Maybe this is an admission of vanity, but when I feel defeated by academia, I rewatch my old aerial performance videos. I think about all the times I fell before finally getting it. How learning hardly ever looks or feels graceful when it’s happening.

This got me thinking about how deeply my years of training in aerial arts have shaped the way I approach research. So here’s my attempt at articulating what one passion taught me about another.

Finding stability in early specialization

During my college’s Accepted Students Day, I saw my first partner acro performance. Something about it, maybe the challenge or the novelty, instantly captivated me. It also helped that one of the first friends I made was a flying trapeze instructor, and together we infiltrated the campus aerial and acrobatics club.

Early on, we were encouraged to try a variety of disciplines: aerial hoop, trapeze, silks, rope, and partner acro. I’d always been naturally flexible but noodle-armed, so anything that required me to hold myself up for long periods was… unappealing. (That means everything but hoop and trapeze, both of which I think of as pretty sitting.) I immediately gravitated toward aerial hoop and chose to specialize in it. It was the only apparatus I ever performed on, and I’ve never regretted not branching out or being what some might call a “one-trick pony.”

I’m someone who, once drawn to something, goes all in. Whether it’s based on instinct or stubbornness (likely both), I tend to stay loyal to my preferences—or, to borrow some jargon from my field, I’m “internally consistent.”

Which brings me to 2017, back when I was an undergraduate. I saw someone give a talk about their gossip study, where they built a multi-player web app to study real-time social interactions. The moment I saw it, I thought this is what I want to do—to build interactive experiments that allow us to study communication and coordination as they unfold.

That talk didn’t just inspire me, it gave me a direction. Since then, I’ve made multi-user web apps my only approach for data collection. It’s not that I’ve mastered it, but I know what excites me and what I aspire to get better at. That clarity has been a compass when everything else feels uncertain.

To make this story even better, four years after seeing that 2017 talk, I began my PhD in January 2021 in the same lab where the speaker had been a graduate student. What could have been a momentary spark had instead lit up a research path, a mentorship-friendship I treasure, and a methodological identity I still feel deeply connected to.

And on a more practical level, it’s also become something I can rely on. If I’m feeling unmotivated or stuck, lost in the weeds of parameterizing a model or interpreting noisy results, I know I can return to the concrete, satisfying act of programming interactive experiments. There’s comfort in the structure of a web app: the sleekness of an interface, the visible progress of something coming together. It grounds me. It reminds me what I can build, what I’m capable of, when everything else feels murky.

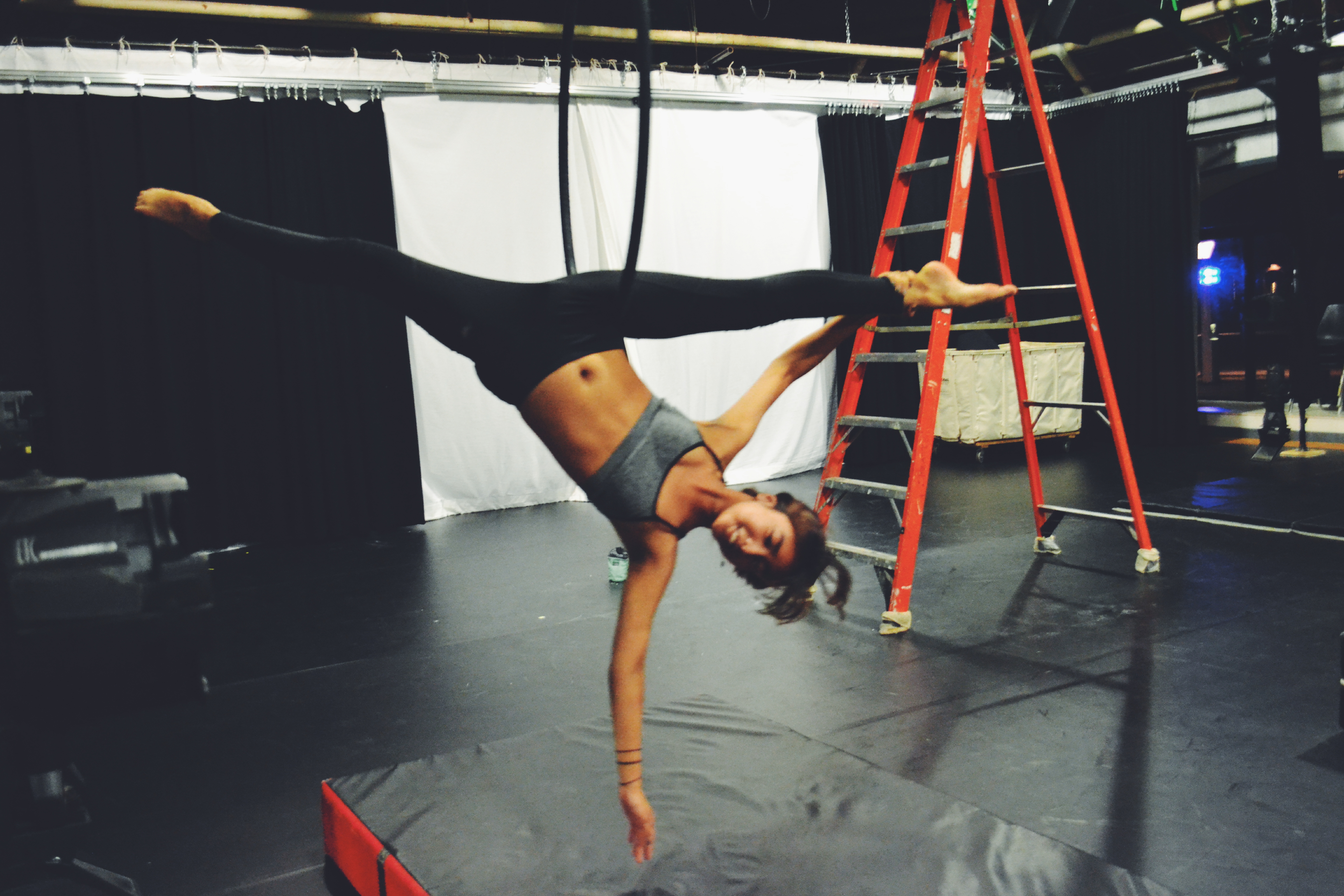

Weaponizing stubbornness to grow

My favorite move I taught myself was the hip hang (pictured above). It may look simple, but getting into it was a whole other story. My body didn’t understand the mechanics. Initial attempts ended with me sliding out of the hoop, bruising my hip again and again until a black spot bloomed where the metal pressed into bone.

I’d get frustrated, try again. Get more frustrated, try harder. For a long time, it felt like I was just failing—like my body did not belong on the hoop in that way (shocker!). But then, one day, something shifted. My muscles solved what my mind couldn’t quite grasp, and I lifted into the shape. Eventually, that bruised spot went numb. Still black, but no longer painful.

Aerial taught me that grit isn’t glamorous. It’s boring. Repetitive. Often invisible. Progress usually feels like stagnation until suddenly it just doesn’t.

Research sometimes feels the same: like you’re spinning your wheels, revisiting the same questions, trying variations that still don’t quite work. But if you stay with it, tweaking your approach and listening to your instincts, you eventually find the hold.

Leveling up to overcome the flatland fallacy

Everyone comes in with a different set of “stats”: strength, flexibility, coordination, musicality, technique. Some people pick things up quickly because they’re strong; others, because they’re fearless or unusually bendy. But no one starts off good at everything. You build capacity one attribute at a time, and as you do, new possibilities unlock. Gain flexibility, and you can enter new shapes. Gain strength, and you can hold positions that were once out of reach.

Research works the same way. We all come in with different skillsets, and growing as a researcher means leveling up in those areas over time. Improving your writing might help you share your findings more clearly. Strengthening your modeling chops might let you ask deeper, more precise questions. Expanding your skill repertoire means expanding what you’re capable of doing and understanding.

This progression reminds me of this paper on the “flatland fallacy” written by Jolly and my PhD advisor. They argue that many psychological theories suffer from an oversimplified, low-dimensional view of complex human phenomena. Like the Flatlanders in Edwin Abbott’s novella—creatures who live in two dimensions and can’t imagine a third—we too can become trapped by the limits of our own cognitive tools. But they suggest that one way out is through developing the technical skills that allow us to build more expressive, higher-dimensional models of behavior.

In other words, leveling up quantitatively isn’t just about checking a box or signaling competence. It’s about expanding the theoretical space we’re able to explore and satisfactorily study. Just as gaining strength or flexibility in aerial lets you access more dynamic movement vocabulary, building fluency in formal modeling, programming, or statistics gives you access to richer and more precise scientific questions.

The more dimensions you can perceive and work in, the more fully you can understand the system you’re trying to model—whether that system is the human mind or the movement of your own body in the air.

Adapting to different management styles

Serving on the aerial club’s executive board exposed me early on to how leadership style shapes group dynamics. I wasn’t president, but for a few years, I worked closely with the people who were. Each one brought a distinct approach to leadership. Some were assertive and highly structured, quick to make decisions. Others were more easygoing and collaborative, inviting input and encouraging flexibility, even if it slowed things down. I saw how those choices affected the club’s morale, participation, and momentum. Too much control could stifle member cooperation and creativity; too little could lead to disorganization and frustration. The best leaders found a balance, or at least knew when to adapt based on the situation and the people involved.

PIs, like club presidents, vary widely in how they lead. Some provide structure and top-down direction; others offer freedom but little guidance. Learning to work under (and around) different styles has helped me navigate research environments with more self-awareness and adaptability. I’ve come to understand what kind of structure helps me thrive, and where I need to create it for myself.

Choreographing my own path

Once I had the basics down, I started choreographing my own routines. There’s something deeply empowering about stringing moves together into a sequence that felt entirely mine. Unlike more formal dance disciplines, where a single choreographer teaches the group a set routine, aerial often encourages independence and experimentation. You pick your own music. You build your own story. You are your own choreographer.

I used to walk to class with earbuds in, listening to the playlist of songs I wanted to perform to (which I’ve posted above). I’d imagine which poses would fit with which lyrics, where a drop might land most dramatically, or how to thread transitions together to tell a story. It was part puzzle, part daydream, part embodiment.

But that creativity didn’t emerge in a vacuum. It was shaped by my constraints: what I could physically pull off without injury. My routines were built around the edges of my ability, which meant they were uniquely mine. The limitations didn’t hinder the work; they shaped it.

Research is like that too. One of the paradoxically liberating and anxiety-inducing things about graduate school is how little structure there really is. There’s no universal PhD syllabus, no choreography to follow. Every PhD is “the same” in that it’s largely shaped by the individual. Just you, your tools, your questions. Your constraints. Maybe your dataset is messy. Maybe your modeling skills aren’t where you want them to be. That doesn’t make your work worse—-it makes it yours.

Leaning into that autonomy, learning to choreograph my own research journey, has helped me feel less overwhelmed by the unknown and more confident in what I can create. Imperfect but uniquely mine.

K (above) and I (below) performing our “Tweedle Dee” move on the lyra (which is another name for aerial hoop!)

K (above) and I (below) performing our “Tweedle Dee” move on the lyra (which is another name for aerial hoop!)

Collaborating closely to form ad-hoc conventions

One of the quirks of aerial, especially compared to more formalized disciplines like ballet, is that there isn’t a universal naming system. In ballet, a tendu is always a tendu. But in aerial, the same move might be called a “gazelle,” a “stag,” or something else entirely.

You can imagine how this lack of standardization can be confusing or inefficient: learning and teaching moves requires you to reach a consensus on a naming convention, to reduce uncertainty. It forces you to describe things precisely, to ask questions, to check your assumptions. It’s not unlike working in interdisciplinary research, where the same term can mean different things to different people (e.g., What is a representation?). You can’t take shared vocabulary for granted. You have to build it.

That lesson became especially clear when I started performing with K, my duo hoop partner for all four years of college. (Also, performing with K was one of my longest-running collaborations to date!)

We learned to mirror, counterbalance each other’s weight, and build shapes together. But more than anything, we learned how to communicate. In the beginning, we had to talk through every detail: what move we were trying, who initiated it, where we’d make contact, and how we’d time our transitions. Communication was constant and deliberate.

And as we developed routines together, we also developed our own internal vocabulary. Since naming conventions in aerial aren’t standardized, especially in duo work, we created a kind of partner-specific shorthand. One example is a move we called “Tweedle Dee,” which we borrowed from a YouTube routine we once saw, where the performers played Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum in an Alice in Wonderland–themed act. To anyone else, that name would be meaningless. But to us, “Tweedle Dee” instantly evoked a full sequence of coordinated movement, who was doing what and when and for how long. It was an abstraction, a compact label for something deeply embodied.

Over time, this vocabulary allowed us to move together more fluidly, without having to explain every detail. Eventually, we didn’t need to talk at all. By the time we performed our final duo act, we were in sync, able to anticipate each other’s timing, weight shifts, and intentions with near-perfect precision.

That shared understanding didn’t just make things easier, it made things better. Our routines reflected a partnership that had been built over years of trust, improvisation, and collaboration. Because our communication and movement were so tightly integrated, our performances had a kind of rhythm and playfulness that felt uniquely us. Compared to solo acts, our routines offered something more unexpected—more dynamic, more relational, more fun to watch (or so I have been told!)

Reflecting on this now, I’m reminded of research on coordination and shared understanding. In particular, McCarthy & Hawkins, et al., 2021 studied how people develop their own shorthand when working together on physical tasks, much like K and I did. They found that over time, people naturally create their own language for complex movements, building up shared understanding through experience. That dynamic felt exactly like our journey: starting with careful, explicit instructions, then gradually building up our own vocabulary that let us move together seamlessly. Our “Tweedle Dee” wasn’t just a name; it was a scaffold for joint understanding and collaborative movement. It was also creative expression that neither of us could have achieved alone.

A group photo of the aerial club from our water-themed show. K and I performed a “mermaid pirate love story” which you can watch here.

A group photo of the aerial club from our water-themed show. K and I performed a “mermaid pirate love story” which you can watch here.

An interdisciplinary community of misfits

One of the most unexpected gifts of aerial was the community it brought me into. Aerial spaces tend to attract people who never quite fit into traditional molds—a safe haven for anyone who’s ever dreamed of abandoning societal expectations and “running off to the circus.” It’s a space where things are more strange, more creative, more free. Everyone is weird in their own way, and no one’s trying to hide it.

Some of us came to the club from dance or gymnastics. Others had been circus performers, ultimate frisbee players, martial artists, or even tree climbers. Everyone brought their own skills, strengths, and styles, and there was room for all of it. That kind of eclectic, non-hierarchical energy made it one of the first spaces where I felt truly comfortable taking up space—not because I was the best, but because being different was the norm.

In academia, finding that kind of community isn’t always easy. The structures are more rigid. The pressure to conform and to be impressive in a specific way is much higher. If you don’t see yourself reflected in your cohort, your department, or your field, it can feel deeply isolating.

But aerial gave me a blueprint for what belonging can feel like. It showed me the power of shared risk, mutual support, and celebrating difference as a strength. That experience informs how I try to show up in academic spaces now: seeking out collaborators who value openness and generosity, mentoring with empathy, and trying, when I can, to carve out small pockets of weirdness, honesty, and community for others.

Curtain call

So maybe it’s not vanity that brings me back to those old performance videos. Maybe it’s a way of remembering who I am and who I’ve always been becoming.

Aerial taught me to persist through pain, to experiment boldly, to communicate with care, and to seek out communities where I feel seen. These lessons have followed me into the lab, into my methodological approaches, into the questions I care about. They shape how I move through academia: not with perfect grace, but with a kind of practiced stubbornness. A relentless willingness to try again.

And when I feel lost or inadequate, I return to those memories, not just for nostalgia, but for perspective. They remind me that the version of me who kept climbing back into the hoop is still here. Just doing a different kind of hanging on. I remember how many times I flailed before I flew. How much of progress looks like failure until, one day, it doesn’t.

Because if you fall enough times and keep getting back up, you don’t just survive. You learn to fly.